Are we living in a Long Walk? Book 2 of the Bachman Books... Let's talk about it.

- Teresa Buzzoni

- Jan 5, 2023

- 7 min read

Last year, I did a lot of reading… I was a self help book away from finding myself. Through this period of self realization and actualization of my habits, I found that the majority of the habits that are character forming are simple. They’re concrete awarenesses about the fundamental success of what makes some people rise to the top and others fall behind in the unforgiving environment that is the real world.

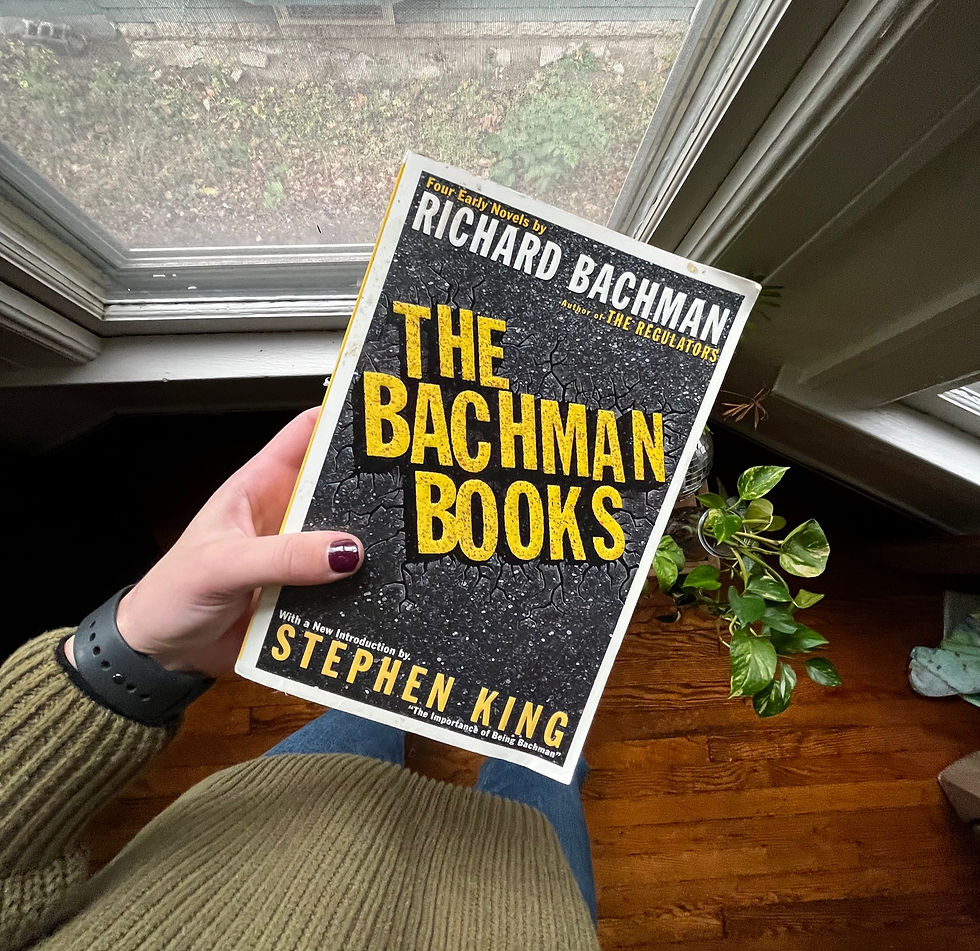

In one of my most prized possessions: The Bachman Books, the four early novels of Richard Bachman (the precursor persona of Stephen King), “The Long Walk” is the second installment of his alter ego stories. Novella style, the book takes a deep dive into what happens in the human brain when dropped from a helicopter into a horizon-less ocean of the human psyche. One of my favorite things about Bachman is the simple manner in which he crafts complete characters, drops them into a situation and allows them to do the narrative work of clawing their way out of it, or succumbing to the violence of the real world.

Like most of Bachman’s early work, “The Long Walk” explores different perspectives on an impossible situation of a test of human spirit. Our main character, Raymond Garraty is a young man emerging from a vehicle and saying his final farewell to his mother

before joining a small flow of men walking towards a sergeant. We find out later the premise of a long walk toward the end of the book: a reaping… a draft… a TV selection of any man in the country to take part in a test of honor and courage with no catch–oh yeah, apart from the officers who show up at your house to take you away, and the guns trained at your back forcing you onward. “Walk or die, that;s the moral of this story. Simple as that. It’s not survival of the physically fittests. That’s where I went wrong when I let myself get into this. If it was, I’d have a fair chance… It isn't man or God. It’s something… in the brain” (Bachman, 191).

Ray Garraty is only sixteen at the time of the walk. Bachman begins the story with very little situational awareness. Our eyes are trained on Ray and his perceptions of the other characters as the story progresses. The story is reminiscent of an original version of a Hunger Games concept–run until you drop. If you drop, you die. Three warnings are your only buffer between life and death. Each of your competitor's strengths brings you one step closer to dying.

When facing down the barrel of death, Garraty thinks in the beginning of his own morality. Now placed in a situation of sure defeat he wonders if “you’re better to take it a day at a time, is all i’m saying. If people just took it a day at a time, they’d be a lot happier,” (Bachman, 169). And perhaps this is true. The clock seems to slow down for Ray as he is stripped from the complexities of life and even the larger game that is the Long Walk. He is one with the road, his companions and the small rations that sit in his pockets.

Just like a boy, Ray yearns for his security in the form of Jan, his girlfriend from home and sometimes from his mother figure. Garraty is a boy at only sixteen, attempting to fill the boots of a man. “He could not even kid himself that everything had not been upfront because it had been. And he hadn’t even done it alone. There were ninety-five other fools in this parade” (Bachman, 171).

I guess there’s a level of clarity that all of the self-help authors have been struggling with. When faced with our own humanity, challenges look small and self admonishment or the toils of living seem meaningless. Garraty, completely removed from a civilization that cheers him away from death and is unscathed by the needless shooting of victims as they collapse, seems entirely withdrawn from empathy. Garraty passes through many towns, searching the crowds for faces that he might recognize. As the walk progresses, he continues to become more and more angry at the faces waving in glee as he suffers, “You wave back at the people who wave to you because that’s the polite thing to do. No one argues very much with anyone else (except for Barkovitch) because that’s also the polite thing to do. It all goes on” (Bachman, 188).

No one seems to question the walk, or why there is impending death for each character except one. No one argues, except Barkovitch. Barkovtich is portrayed as crazy. Accepting his fate, Barkovitch uses his warnings to sit or rest, seemingly defying the expected rules of the Walk. Garraty observes him as he criticizes the walk situation and “caught sight of Barkovich again and wondered if Barkovitch wasn’t really one of the smart ones. With no friends, you had no grief,” (Bachman, 203). It is in Barkovitch’s character that we begin to realize what exactly is happening among the boys.

We find out towards the end of the story that the Long Walk is essentially a metaphor for the Vietnam War… the draft, the information hiding, the camaraderie and the needless killing. In fact, Garraty’s own father was arrested for speaking out against the Walk–a nod to the information war and relinquishing of free speech that the Vietnam War caused. “It would have been a good living if Jim Garraty could have kept his politics to himself. But when you work for the Government, the Government is twice as aware that you’re alive, twice as ready to call in a Squad if things seem a little dicky around the edges. And Jim Garraty had not been much of a Long Walk Booster…It had been eleven years. It had been a neat removal. Odorless, sanitized, pasteurized, sanforized, and dandruff-free” (Bachman, 220). It is here when we are confronted with the reality that the fantasized converges upon our true experience. Stories like the Hunger Games and the Long Walk seem foreign, but when it comes to the dire life and death, they really are not. During the Vietnam War, information and perception was a power that needed to be restricted. Just as the walk existed because of the ultimate punishment for speaking out, it also reveals much about our human truth.

“Death is great for the appetites…why are you so goddamn sure that makes us human beings?... We don’t die, that’s why they’re doing it” (Bachman, 222). The Long Walk was a promise to the guards who shot them and followed orders. It was a revelation to the people who were allowed to place bets and make a quick buck on how long the Walker’s humanity lasted. It existed in the veneration of a single person who would be protected from the struggles of living if they were able to outlast the other ninety nine people.

For Garraty, the question of motivation was all that matters. Ray was introduced as this person who is extremely simple. He wants to kiss and make love to a woman, or see his mother again, but we don’t realize that he’s just a sixteen year old boy. There should be no reckoning with death in his future. There shouldn’t be the realization of life and humanity, and yet there he is, recognizing his reason for walking and observing it in the actions and kindness of the others.

Garraty watches one of his friends, Harkness, get a foot cramp and watches him as Harkness pleads with his eyes to Garraty.

“‘I got a cramp in my foot, man. I don’t know if I can walk on it.’

Harkness’s eyes seemed to be pleading for Garraty to do something… Jan’s voice, her laughter… the time they took his liter brother’s sled… those things were life. Harkness was death. By now Garraty could smell it.

‘I can’t help you,’ Garraty said. ‘You have to do it yourself.’ (Bachman, 207).

The Walk forces the remaining walkers to make the pact abandon one another and fend for themselves despite how much each of them wants to refuse their own survival. Garraty walks only out of fear of the alternative and because he is entirely terrified by the situation. Barkovitch, the killer, seems to walk only for his own survival and the revenge of his life. Percy gives up and walks off the path to his death, taking his own life into his hands as he watches the freedom of the forest. Harkness died because he simply couldn’t continue and gave in to his weakness. Stebbins walks because his father is The Major who runs the show. Each agrees not to help one another because at the end of the day, for each of them, despite their closeness born of their situation, each must survive only for themselves and they respect the weakness or strength that it takes to bow out of life's suffering.

In the conclusion of the book, Garraty is a shell of himself. He and his final companion, Stebbins remain. His best friend, McVries, has just been shot as he fell asleep, unable to continue moving. In his deep fatigued state, Garraty moves “eyes blind, supplicating hands held out before him as if for alms, Garraty walks toward the dark figure. And when the hand touched his shoulder again, he somehow found the strength to run,” (Bachman, 322).

The Long Walk, just as Rage did, forces us to wrestle with the most uncomfortable questions of the certainty of our own peril and the unfortunate fact that in this life we are entirely alone with our own courage. No one is able to prevent death along the way, nor the suffering in our limbs. Our will to survive is the only remedy for our own futility. So, whether we live in the war state of the Vietnam War, or one in which our own democracy seems to cave in on itself, at the end of the day, weather academically, professionally, or in the white walls of our own mind, our only savior is our might and organization of determination that will protect us from eventual doom and give us strength to continue fighting at any cost.

Comments