Rage

- Teresa Buzzoni

- Nov 27, 2022

- 8 min read

Rage

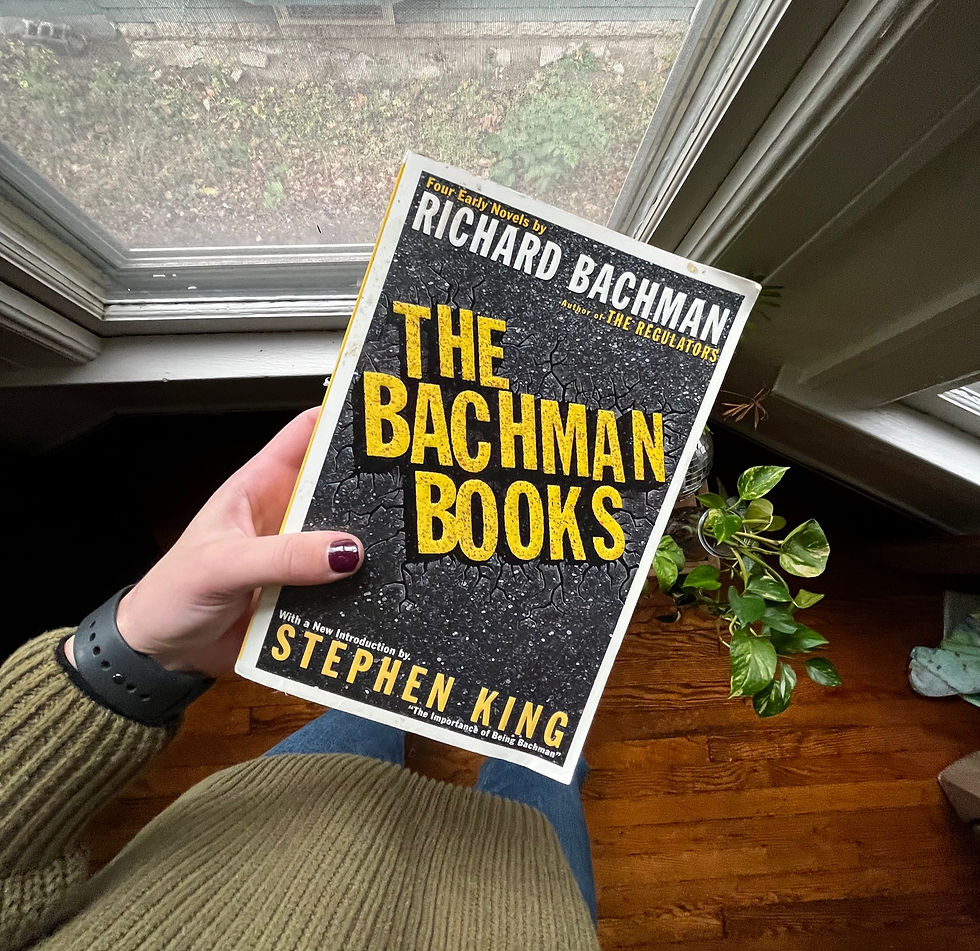

By Richard Bachman

3.75/5

The Introduction

Richard Bachman, we learn, is the alter ego of the world renowned Stephen King. Just as Bruce Wayne allows Batman to live outside the shadows, the King/Bachman duality has allowed King to write freely from glaring social pressures, allowing him to explore the ‘directed delusion’ where he attempts to separate the darkness from the light. The Bachman monomer died, coming to an untimely end as a result of “cancer of the pseudonym, but it was actually shock that killed him: The realization that sometimes people just won’t let you alone (page v, of the intro). His split personality allowed Bachman to wrestle with the question of what line divides human nature from humanity, and reaches into the unknown with questions of what reality would look like if the violence within were released.

Bachman’s musings teeter between reality and the perfect construction of insanity. Bachman prefaces his talent for writing, warning the reality to be so persuasive that: “if there is anyone out there reading this who feels an urge to pick up a gun and emulate Charlie Decker, don’t be an asshole. Pick up a pen, instead. Or pick up a shovel. Or any damned thing. Violence is like poison ivy–the more you scratch it the more it spreads (vi). Yet, as I came to discover, the scariest thing about a Bachman/King novel is that it is in fact fascinating.

Rage

Fascinating is a carefully chosen word. In Rage, there is nothing inherently wrong or right. The story begins with a boy, Charles Decker, with a questionable backstory being expelled from his school for having beaten his professor to near vegetation out of pure rage, with no other explanation. And yet, our minds beg for a reason. We’ve been trained to ask for more reason, because no one in their right mind could commit such an act devoid of a scapegoat.

At the beginning of the novel, we meet Charles Decker, a troubled teen who has some anxieties, but nothing inherently wrong. We see the world through his eyes, as if looking through one of those 25 cent observers at the Statue of Liberty. Through a pair of gaping holes into his life, we are surrounded by a darkness which confuses and obliterates our vision of anyone else’s perspective. It is too painful not to agree with Charlie, or place blame or villandry on any one character. Throughout the exposition, Bachman is exploiting the questioning facets of our personality, which ponders if life is as it is meant to be. Pulling on our flaws, we begin to commiserate slightly with Charlie. After all, he’s just been kicked out of school, but for beating a teacher. Maybe that teacher was in the wrong. Poor kid. “And I stand here before you (metaphorically speaking, again) and tell you I’m perfectly sane. I do have one slightly crooked wheel upstairs, but everything else is ticking along just four-o, thank you very much. So they. How do we understand them? We have to discuss that, don’t we?” (28).

The whole book is a dialogue of ‘them’. When Charlies shoots and kills two instructors in cold blood, taking a classroom hostage, the most jarring effect emerges when the children remain nearly unfazed. Here is where the decay begins to set in. The student’s humanities tumble, one after another, like dominoes. Grace Stanner begins encouraging Charlie to murder people (61). Two girls fight in a circle as they force the truths from one another (64). People are drowning kittens in the bathtub and having abortions (70). Some students attempt to stop the insanity that is quickly unfolding, calling out “You’re all going just as crazy as him,” but the entire time, Charlie is sitting there with a pistol, recounting the trauma that made him that way, and he doesn’t seem crazy at all (71).

Charlie is human, after all. He experiences a moment of recognition for the life that he took, when “I suddenly needed to scream. I had taken her life, I had snuffed her, put a bullet in her head and spilled out algebra” (72). Through the recounting of his story, we learn that he was beaten and bullied for his clothing, abused at the hands of his father, and suffering emotional and physical violence in most aspects of his life. However, his resentment is paused, just like his cries for help by the lack of recognition that he receives. He never seems to find the light of day. The assaults of his bully are wiped clean when it is revealed that one of his assailants was hit by a car, dying in a tragic accident. Yet, the untimely and irreversible death of his childhood bully, killed by a car, seems to cloud the truth surrounding his character. Does the tragedy of an untimely death excuse one’s torment of another?

Interestingly, many of the girls in the class seem to feel safe around Charlie, or perhaps freed. The situation allows them to open up about their virginity and explore how the concept makes them feel objectified and diminished, describing how “sometimes, I feel like a doll. Not really real. You know it? I fix my hair and every now and then I have to hem a skirt… and it all just seems very fake.. Do you ever feel like that, Charlie?’ I thought about it carefully. ‘No,’ I said ‘I can’t remember that ever crossing my mind’” (97). By taking the classroom hostage, Charlie has broken down the wall of anxiety, allowing each of his students–his hostages–to become freed in some way. “I wore my shortest skirt. My powder-blue one. And a thin blouse. Later on. We went out back. And that seemed real. He wasn’t polite at all. Or that I might get pregnant. I felt alive” (98). So what? Even the good girls go bad sometimes? Similar to the Lord of the Flies, when the parameters of what is considered crazy are removed, each of the students is willingly offering material to prove or disprove their sanity. It doesn't make sense for a girl who had everything to need to have sex in the dark with a man she’d never met, but “this has been better, Charlie” (99). Charlie’s darkness allows them to express their own in the setting which forces each character to examine their own evil, and introspect, examining the confines of their lives.

One for example, Irma Bates, who walks out of the bathroom without a nod towards the gun that Charlie has trained to her head, returns to the classroom willingly. She is not fearful of her death, but seemingly exists in a shell of herself that seems more willing to give up life than Charlie. Despite his act of insanity, Charlie is left to marvel at the students, “how could she let that beyond the walls of herself? How could she say that? But there was nothing in the faces that I saw to echo that thought” (99). In so many ways, Charlie is being surprised by the darkness that is revealed within each of his classmates, because there is something inherently dark or secret about each one. We feel Charlie’s shock… remember? We’re watching only through the two gaping holes of our 25 cent observer here.

At the end, Charlie sees his mistake not as having killed two people or trapped a classroom. We don’t really see that as the problem either, because Charlie has opened a much larger set of floodgates: “I had brought all the brooms to life, but now where was the kindly old magician to say abracadabra backward and make them go back to sleep? Stupid, stupid” (112).

Throughout flashbacks of the novel, we are able to craft a more complete observation and diagnosis of Charlie. Since the first page, we’ve known of his troubling stomach issues that prevent him from keeping his breakfast down. Charlie is a highly anxious person, and perhaps has a manic depression that has gone ignored and untreated by the same school professionals that view him as delusional and maniacal. However, there is continued evidence in his backstory of opportunities in which he could have been saved, or perhaps stopped. The piling on of troubles have reached their tipping point: Charlie does not care to be saved.

As a boy, Charlie was victim to numerous attacks by his father. In one such instance, Charlie was a little boy, tossing stones at glass windows, breaking them in youthful rebellion. He is watching his mother play piano through the panes. He intentionally is snapping the glass, yet as a child, is he proceeding in innocence or of childhood impishness? Charlie’s father takes him and shakes him around, slamming him to the ground before his mother is able to save him. Following this incident, numerous hunting trips, school incidents, belting arguments and physical abuses reach a climax. Charlie stands up to his father after getting beaten up by some of the bullies at his school. Facing the even larger bully, his parent, Charlie knows that he will win the fight, in fact, he will win because of the darkness taught to him by his father. “Maybe he had forgotten or never knew that little boys grow up remembering every blow and word of scorn, that they grow up and want to eat their fathers alive” (117).

The anger, pain and anguish which Charlie faced is now suppressed, recalled among good memories of losing his virginity, getting high and meeting girls. Yet, there is still chaos in the classroom. Each time that we phase in and out from a story of Charlie’s past, the classroom has gone slightly more crazy. Ted, one of the characters in the room, is being physically assaulted and overpowered by two of the boys in the classroom holding him down while Sylvia, now scorned, moves toward him, beginning to beat him. “Please,’ Ted said, ‘please, Charlie.’ Sylvia had joined the little circle around him…they were moving around him in a slow kind of dance that was nearly beautiful” (123). These students harm Ted to the point to which he is the only student unable to walk out of the classroom at the end when Charlie allows them to leave. He and Charlie remain–Ted slumped against the wall, and Charlie, perched on the desk.

Following the racing events of raging highs and scooping lows, Bachman leaves us to wrestle with a new problem. We have been racing through mental conversations and dialogue for nearly three hours, and a hundred pages of intrigue, and yet the story abruptly ends once these students leave. Charlie’s leverage is gone, and with only two options, surrendering or death, Charlie ends up exactly where we think he might: in a mental institution. Several memos suggest the electric chair or execution. He is, in fact, a murderer, school shooter, and vengeful person, who killed three people and nearly died at the hands of a sniper.

But…

His friends still root for him. We still wish that he might have had a life. Throughout the story, Charlie really never experienced a life. His four walls were white and vacant of true feeling. While he loved his mother, the abuse never left those memories pure. The school system failed him to the point where they were choosing to give up on him in the beginning. Or maybe the school was right. Maybe Charlie should have been locked up before being able to kill two people and hold hostage an entire classroom of children. The fact is, that Bauchman has made us question it. We aren’t sure of what our humanity is telling us to do, because there is no one person that we can side with. We cannot place our blame on anyone but ourselves for making enemies of not realizing the pain and struggle. We cannot blame a system made of unhappy people who all have something to hide. But what do we do? Is there anything we can do? Or are we all just like Bauchman, living in a directed delusion of someone else’s story… “Sometimes, I wonder about that a lot.” (ix).

Comments