A BRIEF HISTORY

Sea Island Cotton fibers within a boll are tightly interwoven together to form a collection of five balls wound together. Just like the crop, the interwoven history of sea island cotton involves multiple threads of history from different parts of the globe twined together in a shared history. To better understand the paths and influences of cotton today, a walk down memory lane helps illuminate the complexities of a history of dark times.

In brief, the 1700s demonstrated the emergence of sea island cotton. Pre-Columbian exchange, seeds were exchanged in the Caribbean, finding themselves on the American continent by 1790, when William Elliot imported the Gossypium Barbadense variety of cotton into Myrtle Bank on Hilton Head, South Carolina. The explosion of sea island cotton as well as the traditional varieties boomed from the creation of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793.

From there, the sea island cotton crop began growing in James, Johns, Wadmalaw, Edisto, St. Helena and Port Royal. England began developing power looms in Lancashire. From 1850-1860, more than 500 million pounds of sea island cotton were exported from Charleston S.C., to England, amassing a value of over four billion dollars. In 1858, Senator Hammond gave his famous Cotton is King speech, saying “Save the South, No, you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is king.” His sentiments were obviously true, as Britain was importing 88% of sea island cotton from the Americas.

Two-thirds of the cotton being produced in America was being grown in the “Cotton Belt.” An exclusive top 1% of plantation owners, naming themselves the Sons of Beaufort produced massive amounts of sea island cotton. The other 99% of farmers owned fewer than 100 slaves, and were not operating on the same scale as the Sons.

The Boll Weevil was almost the end of sea island cotton. Nearly driving extinction, the boll weevil entered the United States from Mexico in 1892, reaching South Carolina in 1918.

Image: The Boll Weevil

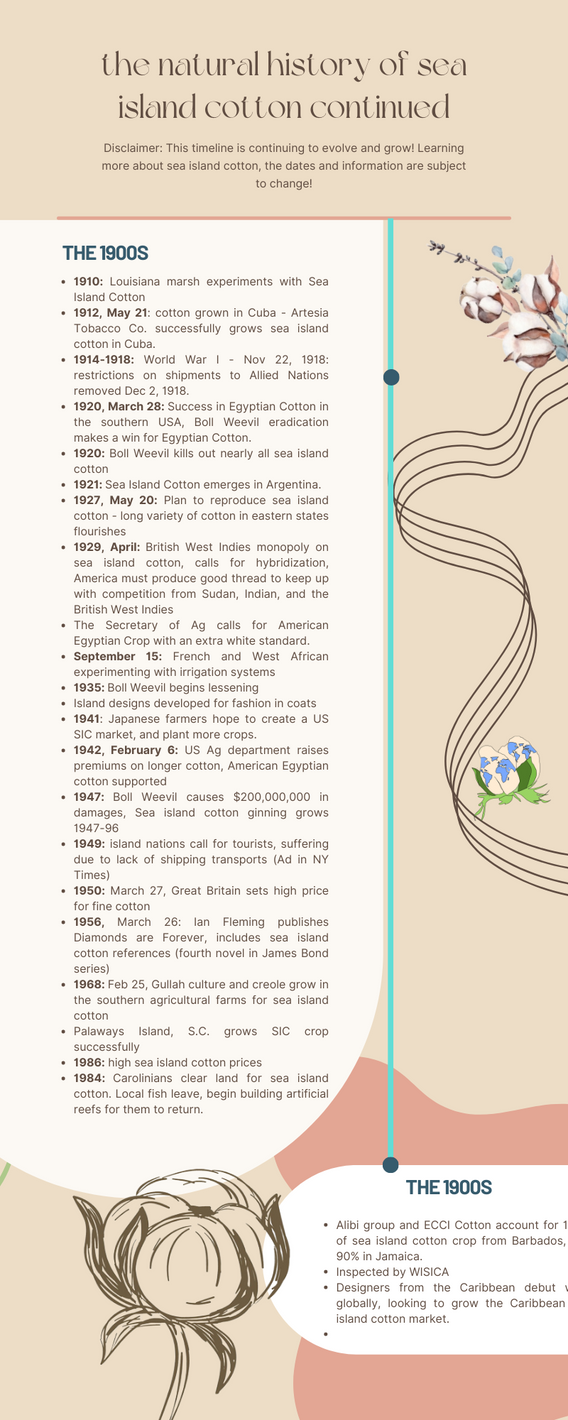

Sea island cotton began to be grown in Cuba by the Artesia Tobacco Company. When World War I began, restrictions were placed on shipments to the Allied Nations. The fine sea island cotton fibers were used for high quality uniforms for officers and commanders. Finally, on December 2, 1918, they were removed, allowing the crops to resume production for commercial expansion. Yet, in the Americas, the boll weevil had nearly decimated the crop. At this time, the Egyptian strain of sea island cotton sprang into the center stage. In fear, the Secretary of Agriculture in the United States called for sea island cotton crops with an extra white standard. By September 15, the French and West Indian groups were experimenting with irrigation systems. In 1935, the boll weevil ceased, and Caribbean designers began experimenting with coat fashions. By 1942, the U.S. government had raised premiums on longer cotton, in great competition with Egyptian cotton. However, in total, the boll weevil by 1947, had caused $200,000,000 in damages.

Ian Fleming, the creator of the James Bond character published his novel, “Diamonds are Forever '', referencing sea island cotton from his time as a navy man in the caribbean. In 1968, the southern Gullah culture was emerging and continuing to grow sea island cotton successfully. By 1984, South Carolinians were working to clear land for sea island cotton. The local fish left as a result of the changes, so fishermen began building some of the first artificial reefs for them to return to.

Flash forward to today, the Albini group and ECCI cotton account for 100% of sea island cotton produced in Barbados and 90% of the cotton created in Jamaica. It is all inspected by a company called WISICA, or the West Indian Sea Island Cotton Association. Designers from the Caribbean have begun debuting their work globally, looking to grow the Caribbean authenticity among the global fashion industry.

Source: Dr. Richard Porcher, The Citadel

Dr. Porcher and several botanists including Tom Austen with the Edisto Island Trust are attempting to revise the history surrounding cotton. Hobbyists and historics are attempting to regrow the crop, but because of the incredible labor intensity and small yield, biologists and historians are wondering if the crop is even feasible. Farms like the ones in the West Indies where labor and government are different may remain the sole producers of sea island cotton, unless someone learned how to grow it differently.

A Brief Sea Island Cotton Story Timeline